| What’s in a name |

|

The "Byzantine Empire" is the term conventionally used to describe the Greek-speaking Roman Empire during the Middle Ages, centered at its capital in Constantinople. In certain specific contexts, usually referring to the time before the fall of the Western Roman Empire, it is also often referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire. There is no consensus on the starting date of the Byzantine period. Some place it during the reign of Diocletian (284-305) due to the administrative reforms he introduced, dividing the empire into a pars Orientis and a pars Occidentis. Others place it during the reign of Theodosius I (379-395) and Christendom's victory over paganism, or, following his death in 395, with the division of the empire into Western and Eastern halves. The term "Byzantine Empire"The name Byzantine Empire is derived from the original Greek name for Constantinople; Byzantium. The name is a modern term and would have been alien to its contemporaries. The term Byzantine Empire was invented in 1557, about a century after the fall of Constantinople by German historian Hieronymus Wolf, who introduced a system of Byzantine historiography in his work Corpus Historiae Byzantinae in order to distinguish ancient Roman from medieval Greek history without drawing attention to their ancient predecessors. Standardization of the term did not occur until the 18th century, when French authors such as Montesquieu began to popularize it. Hieronymus himself was influenced by the rift caused by the 9th century dispute between Romans (Byzantines as we render them today) and Franks, who, under Charlemagne's newly formed empire, and in concert with the Pope, attempted to legitimize their conquests by claiming inheritance of Roman rights in Italy thereby renouncing their eastern neighbors as true Romans. The Donation of Constantine, one of the most famous forged documents in history, played a crucial role in this. Henceforth, it was fixed policy in the West to refer to the emperor in Constantinople not by the usual "Imperator Romanorum" (Emperor of the Romans) which was now reserved for the Frankish monarch, but as "Imperator Graecorum" (Emperor of the Greeks) and the land as "Imperium Graecorum", "Graecia", "Terra Graecorum" or even "Imperium Constantinopolitanus". This served as a precedent for Wolf who was motivated, at least partly, to re-interpret Roman history in different terms. Nevertheless, this was not intended in a demeaning manner since he ascribed his changes to historiography and not history itself. Later a derogatory use of 'Byzantine' was developed.

|

––– ♦ –––

| Early history |

|

Constantinople was founded in 324 by Constantine I, on the location of the ancient colony of Megara, Byzantium. The dedication of the city was celebrated in 330. The transfer of the capital from Rome to Constantinople, combined with the gradual shift of political power from West to East marks the beginning of the Byzantine Empire. Constantinople remained the capital until its final fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, representing the symbol of Byzantine identity and survival. The Eastern Empire was largely spared the difficulties of the west in the 3rd and 4th centuries, in part because urban culture was better established there and the initial invasions were attracted to the wealth of Rome. Throughout the 5th century, various invasions conquered the western half of the empire, but at best could only demand tribute from the eastern half. Theodosius II enhanced the walls of Constantinople, leaving the city impenetrable to attacks: it was to be preserved from foreign conquest until 1204. His Empire collapsed and Constantinople was free from his menace forever, starting a profitable relationship with the remaining Huns, who often fought as mercenaries in Byzantine armies of the following centuries. In this age, the true chief in Constantinople was the Alan general Aspar. Leo I managed to free himself from the influence of the barbarian chief favoring the rise of the Isauri, a crude semi-barbarian tribe living in Roman territory, in southern Anatolia. Aspar and his son Ardabur were murdered in a riot in 471, and thenceforth Constantinople was to be free from foreign influence for centuries. Leo was also the first emperor to receive the crown not from a general or an officer, as in the Roman tradition, but from the hands of the patriarch of Constantinople. This habit became mandatory as time passed, and in the Middle Ages the religious characteristic of the coronation had totally substituted the old form. First Isaurian emperor was Tarasicodissa, who was married by Leo to his daughter Ariadne (466) and ruled as Zeno I after the death of Leo I's son, Leo II (autumn of 474).  Zeno was the emperor when the empire in the west finally collapsed in 476, as the barbarian general Odoacer deposed emperor Romulus Augustus without replacing him with another puppet. In 468 an attempt by Leo I to conquer again North Africa and Carthage from the Vandals had failed mercilessly, showing how feeble were the military capabilities of the Eastern Empire. At that time, the Western Roman Empire was already restricted a small part of Italy: Britain had fallen to Angles and Saxons, Spain to Visigoths, Africa to Vandals and Gaul to Franks (in other words, Germans all over Europe: the beginning of the Middle Ages). To recover Italy, Zeno could only negotiate with the Ostrogoths of Theodoric, who had been settled in Moesia: he sent the barbarian king in Italy as magister militum per Italiam ("chief of staff for Italy"). Since the fall of Odoacer in 493 Theodoric, who had lived in Constantinople in his youth (and had become Roman Consul), ruled over Italy of his own, though saving a merely formal obedience to Zeno. He revealed himself as the most powerful Germanic king of that age, but his successors were greatly inferior to him and their kingdom of Italy started to decline in the 530s. In 475 Zeno was deposed by a plot who elevated one Basiliscus (the general defeated in 468) to the throne, but twenty months after Zeno was again emperor. But he had to face the menace coming from his Isaurian former official Illo and the other Isaurian Leontius, who was also elected rival emperor. Zeno finally prevailed  One of the most efficient rulers wes Anastasius I who revealed himself to be an energic reformer and able administrator. He perfected Constantine I's coin system by definitively setting the weight of the copper follis, the coin used in most everyday transactions. He also reformed the taxation system: at his death the State Treasury contained the enormous sum of 320,000 pounds of gold. |

––– ♦ –––

| Justinian and his successors |

The reign of Justinian I, which began in 527, saw a period of extensive Imperial conquests of former Roman territories (indicated in green on the map below). The 6th century also saw the beginning of a long series of conflicts with the Byzantine Empire's traditional early enemies, such as the Persians, Slavs and Bulgars. Theological crises, such as the question of Monophysitism, also dominated the empire.Justinian I had already probably exerted effective control under the reign of his predecessor, Justin I (518-527). This latter was a former officer in the Imperial Army who had been chief of the Guards to Anastasius I, and had been proclaimed emperor (when almost 70) after Anastasius's death. Justinian was the son of a peasant from Illyricum, but also a nephew of Justin's, and later made his adoptive son. Justinian would become one of the most refined spirits of his century, inspired by the dream of the re-creation of Roman rule over all the Mediterranean world. He reformed the administration and the law, and, with the help of brilliant generals such as Belisarius and Narses, temporarily regained some of the lost Roman provinces in the west, conquering much of Italy, North Africa, and a small area in southern Spain. In 532 Justinian secured for the Empire peace on the Eastern frontier by signing an "eternal peace" treaty with the Sassanid Persian king Khosrau I; however this required in exchange the payment of a huge annual tribute in gold. Justinian's conquests in the West began in 533, when Belisarius was sent to reclaim the former province of Africa with a small army of some 18,000 men, mainly mercenaries. Whereas an earlier 468 expedition had been a dismaying failure, this new venture was to prove a success, the kingdom of the Vandals at Carthage lacking the strength of former times under King Gaiseric. The Vandals surrendered after a couple of battles, and Belisarius returned to a Roman triumph in Constantinople with the last Vandal king, Gelimer, as his prisoner. However the reconquest of North Africa would take a few more years to stabilize and it was not until 548 that the main local independent tribes were subdued. In 535 Justinian launched his most ambitious campaign, the reconquest of Italy, at that time still ruled by the Ostrogoths. He dispatched an army to march overland from Dalmatia while the main contingent, transported on ships and again under the command of Belisarius, disembarked in Sicily and conquered the island without much difficulty. The marches on the Italian mainland were initially victorious and the major cities, including Naples, Rome and the capital Ravenna, fell one after the other. The Goths seemingly defeated, Belisarius was recalled to Constantinople in 541 by Justinian, bringing with him the Ostrogoth king Witiges as a prisoner in chains. However, the Ostrogoths and their supporters were soon reunited under the energic command of Totila. The ensuing Gothic Wars were an exhausting series of sieges, battles and retreats which consumed almost all the Byzantine and Italian fiscal resources, impoverishing much of the countryside. Belisarius was recalled by Justianian, who had lost trust in his preferred commander. At a certain point the Byzantines seemed on the verge of losing all the positions they had gained. After having neglected to provide sufficient financial and logistical support to the desperate troops under Belisarius's former command, in the summer of 552 Justinian gathered a massive army of 35,000 men, mostly Asian and Germanic mercenaries, to be applied to the supreme effort. The astute and diplomatic eunuch Narses was chosen for the command. Totila was crushed and killed at Busta Gallorum; Totila's successor, Teias, was likewise defeated at the Battle of Mons Lactarius (central Italy, October 552). Despite of continuing resistance from a few Goth garrisons, and two subsequent invasions by the Franks and Alamanni, the war for the reconquest of the Italian peninsula was at an end.Justinian's program of conquest was further extended in 554 when a Byzantine army managed to sieze a small part of Spain from the Visigoths. All the main Mediterranean islands were also now under the Byzantine control. Aside from these conquests, Justinian updated the ancient Roman legal code in the new Corpus Juris Civilis (although it is notable that these laws were still written in Latin, a language which was becoming archaic and poorly understood even by those who wrote the new code). By far the most significant building of the Byzantine Empire is the great church of Hagia Sophia (Church of the Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople (532-37), which retained a longitudinal axis but was dominated by its enormous central dome. Seventh-century Syriac texts suggest that this design was meant to show the church as an image of the world with the dome of heaven suspended above, from which the Holy Spirit descended during the liturgical ceremony.  The precise features of Hagia Sophia's complex design were not repeated in later buildings; from this time, however, most Byzantine churches were centrally planned structures organized around a large dome; they retained the cosmic symbolism and demonstrated with increasing clarity the close dependence of the design and decoration of the church on the liturgy performed in it. Under Justinian's reign, the Church of Hagia Sofia was constructed in the 530s. This church would become the centre of Byzantine religious life and the centre of the Eastern Orthodox form of Christianity. The sixth century was also a time of flourishing culture (although Justinian closed the university at Athens), producing the epic poet Nonnus, the lyric poet Paul the Silentiary, the historian Procopius and the natural philosopher John Philoponos, among other notable talents. The conquests in West meant the other parts of the Empire were left almost unguarded, although Justinian was a great builder of fortifications throughout all his reign and the Byzantine territories. Khosrau I of Persia had as early as 540 broken the pact previously signed with Justinian, destroying Antiochia and Armenia: the only way the emperor could devise to forestall him was to increase the sum paid out every year. The Balkans were subjected to repeated incursions, where Slavs had first crossed the imperial frontiers during the reign of Justin I, taking advantage of the sparsely-deployed Byzantine troops to press on as far as the Gulf of Corinth. The Kutrigur Bulgars had also attacked in 540. The Slavs then invaded Thrace in 545 and in 548 assaulted Dyrrachium, an important port on the Adriatic Sea. In 550 the Sclaveni pushed on as far to reach within 65 kilometers of Constantinople itself. In 559 the Empire found itself unable to repel a great invasion of Kutrigurs and Sclaveni: divided in three columns, the invaders reached the Thermopylae, the Gallipoli Peninsula and the suburbs of Constantinople. The Slavs come back worried more by the intact power of the Danube Roman fleet and of the Utigurs, paid by the Romans themselves, than the resistance of an ill-prepared Imperial army. This time the Empire was safe, but in the following years the Roman suzerainty in the Balkans was to be almost totally overwhelmed.Soon after the death of Justinian in 565, the Germanic Lombards, a former imperial foederati tribe, invaded and conquered much of Italy. The Visigoths conquered Cordoba, the main Byzantine city in Spain, first in 572 and then definitively in 584: the last Byzantine strongholds in Spain were swept away twenty years later. The Turks, one of the deadliest enemies of future Byzantium, had appeared in Crimea, and in 577 a horde of some 100,000 Slavs had invaded Thrace and Illyricum. Sirmium, the most important Roman city on the Danube, was lost in 582, but the Empire managed to mantain control of the river for several more years, though it increasingly lost control of the inner provinces. Justinian's successor, Justin II, refused to pay the tribute to the Persians. This resulted in a long and harsh war which lasted until the reign of his successors Tiberius II and Maurice, and focused on the control over Armenia. Fortunately for the Byzantines, a civil war broke out in the Persian Kingdom: Maurice was able take advantage of his friendship with the new king Khosrau II (whose disputed accession to the Persian throne had been assisted by Maurice) in order to sign a favourable peace treaty in 591, which gave the Empire control over much of Persian Armenia. Maurice reorganized the remaining possessions in the West into two Exarchates, those of Ravenna and Carthage, attempting to increase their capability in self-defence and delegating them much of the civil authority. |

––– ♦ –––

| The Difficult Years |

|

The Avars and later the Bulgars overwhelmed much of the Balkans, and in the early 7th century the Persians invaded and conquered Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Armenia. The Persians were defeated and the territories were recovered by the emperor Heraclius in 627, but the unexpected appearance of the newly-converted and united Muslim Arabs (the "Saracens") took by surprise an empire exhausted by the titanic effort against Persia, and the southern provinces were all overrun. The Empire's most catastrophic defeat of this period was the Battle of Yarmuk, fought in Syria. Heraclius and the military governors of Syria were slow to respond to the new threat, and Byzantine Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and the Exarchate of Africa were permanently incorporated into the Muslim Empire in the 7th century, a process which was completed with the fall of Carthage to the Caliphate in 698. The Lombards continued to expand in northern Italy, taking Liguria in 640 and conquering most of the Exarchate of Ravenna in 751, leaving the Byzantines with control only of small areas around the toe and heel of Italy, plus some semi-independent coastal cities like Venice, Naples, Amalfi and Gaeta. The empire's loss of territory was offset to a degree by consolidation and an increased uniformity of rule. The emperor Heraclius fully Hellenized the empire by making Greek the official language, thus ending the last remnants of Latin and ancient Roman tradition within the Empire. The use of Latin in government records, Latin titles such as Augustus and the concept of the empire being one with Rome fell into abeyance, allowing the empire to pursue its own identity. Many historians mark the sweeping reforms made during the reign of Heraclius as the breaking-point with Byzantium's ancient Roman past; it is common to refer to the empire as "Byzantine" instead of "East Roman" from this point onwards. Religious rites and expression within the empire were now also noticeably different from the practices upheld in the former imperial lands of western Europe. Within the empire, the southern Byzantine provinces differed significantly in culture and practice from those in the north, observing Monophysite Christianity rather than Chalcedonian Orthodox. The loss of the southern territories to the Arabs further strengthened Orthodox practices in the remaining provinces.Constans II (reigned 641 - 668) sub-divided the empire into a system of military provinces called thémata (themes) in an attempt to improve local responses to the threat of constant assaults. Outside of the capital urban life declined, while Constantinople grew to become the largest city in the Christian world. Several attempts to conquer Constantinople by the Arabs failed in the face of the Byzantines' superior navy, the Byzantines' monopoly over the still-mysterious incendiary weapon (Greek fire), the strong city walls, and the skill of Byzantine generals and warrior-emperors such as Leo III the Isaurian (reign 717 - 741). Once the assaults were repelled, the empire's recovery resumed.In his landmark work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the 18th century historian Edward Gibbon depicted the Byzantine Empire of this time as effete and decadent. However, by an alternate examination the Byzantine Empire can be regarded instead a military superpower of the early Middle Ages. Factors contributing to this view include its heavy cavalry (the cataphracts), subsidization (albeit inconsistent) of a free and well-to-do peasant class forming the basis for cavalry recruitment, the extraordinarily in-depth defense systems (the themes), the use of subsidies to play its enemies against one another, prowess at intelligence-gathering, a communications and logistics system based on mule trains, a superior navy (although often under-funded), and rational military strategies and doctrines (not dissimilar to those of Sun Tzu) that emphasized stealth, surprise, swift maneuvering and the marshaling of overwhelming force at the time and place of the Byzantine commander's choosing.After the siege of 717 in which the Arabs suffered horrific casualties, the Caliphate were no longer a serious threat to the Byzantine heartland. It would take a different civilization, that of the Seljuk Turks, to finally drive the imperial forces out of eastern and central Anatolia. IconoclasmThe 8th century was dominated by the controversy and religious division over iconoclasm. Icons were banned by Emperor Leo III, leading to revolts by iconophiles throughout the empire. After the efforts of Empress Irene, the Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshiped. Irene also attempted a marriage alliance with Charlemagne, which would have united the two empires, thus recreating the Roman Empire (the two European empires both claimed the title) and creating a European superpower comparable to ancient Rome. These plans were destroyed when Irene was deposed. The iconoclast controversy returned in the early 9th century, only to be resolved once more in 843 during the regency of Empress Theodora. These controversies further contributed to the disintegrating relations with the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, both of which continued to increase their independence and power. |

––– ♦ –––

| The “Apogee” |

|

The empire reached its height under the Macedonian emperors of the late 9th, 10th and early 11th centuries. During these years the Empire held out against pressure from the Roman church to remove Patriarch Photios, and gained control over the Adriatic Sea, parts of Italy, and much of the land held by the Bulgarians. The Bulgarians were completely defeated by Basil II in 1014. The Empire also gained a new ally (yet sometimes also an enemy) in the new Varangian state in Kiev, the Rus, from which the empire received an important mercenary force, the Varangian Guard. In 1054, relations between Greek-speaking Eastern and Latin-speaking Western traditions within the Christian Church reached a terminal crisis. There was never a formal declaration of institutional separation, and the so-called Great Schism actually was the culmination of centuries of gradual separation. From this split, the modern (Roman) Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches arose. Like Rome before it, though, Byzantium soon fell into a period of difficulties, caused to a large extent by the growth of the landed aristocracy, which undermined the theme system. Facing its old enemies, the Holy Roman Empire and the Abbasid caliphate, it might have recovered, but around the same time new invaders appeared on the scene who had little reason to respect its reputation. The Normans finally completed the Byzantine expulsion from Italy in 1071 due to an ostensible lack of Byzantine interest in sending any support to Italy, and the Seljuk Turks, who were mainly interested in defeating Egypt under the Fatimids, still made moves into Asia Minor, the main recruiting ground for the Byzantine armies. With the surprise defeat at Manzikert of emperor Romanus IV in 1071 by Alp Arslan, sultan of the Seljuk Turks, most of that province was lost. A partial recovery was made possible after Manzikert by the rise to power of the Komnenian dynasty. The first emperor of this line, Alexius Komnenos, whose life and policies would be described by his daughter Anna Komnene in the "Alexiad", began to reestablish the army on the basis of feudal grants (próniai) and made significant advances against the Seljuk Turks. His plea for western aid against the Seljuk advance brought about the First Crusade, which helped him reclaim Nicaea but soon distanced itself from imperial aid. Later crusades grew increasingly antagonistic.

Although Alexius' grandson Manuel I Comnenus was a friend of the Crusaders, neither side could forget that the other had excommunicated them, and the Byzantines were very suspicious of the intentions of the Roman Catholic Crusaders who continually passed through their territory. |

––– ♦ –––

| The End of the Empire |

|

The Germans of the Holy Roman Empire and the Normans of Sicily and southern Italy continued to attack the empire in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Italian city states, who had been granted trading rights in Constantinople by Alexius, became the targets of anti-Western sentiments as the most visible example of Western "Franks" or "Latins." The Venetians were especially disliked, even though their ships were the basis of the Byzantine navy. To add to the empire's concerns, the Seljuks remained a threat, defeating Manuel at Myriokephalon in 1176. Frederick Barbarossa attempted to conquer the empire during the Third Crusade, but it was the Fourth Crusade that had the most devastating effect on the empire. Although the stated intent of the crusade was to conquer Egypt, the Venetians took control of the expedition when their chieftains could not pay the transport of the troops, and under their influence the crusade captured Constantinople in 1204. As a result a short-lived feudal kingdom was founded (the Latin Empire), and Byzantine power was permanently weakened. At this time the Serbian Kingdom under the Nemanjic dynasty grew stronger with the collapse of Byzantium, forming a Serbian Empire in 1346. After the fall of Constantinople, three successor states were left: the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Trebizond, and the Despotate of Epirus. The first, controlled by the Palaeologan dynasty, managed to reclaim Constantinople in 1261 and defeat Epirus, reviving the empire but giving too much attention to Europe when the Asian provinces were the primary concern and a new threat the Ottoman Turks appeared in the western part of Minor Asia. For a while the empire survived simply because the Muslims were too divided to attack, but eventually the Ottomans overran all but a handful of port cities. The Byzantines appealed to the west for help, but they would only consider sending aid in return for reuniting the churches. Church unity was considered, and occasionally accomplished by law, but the Orthodox citizens would not accept Roman Catholicism. Some western mercenaries arrived to help, but many preferred to let the empire die, and did nothing as the Ottomans picked apart the remaining territories. Constantinople was initially not considered worth the effort of conquest, but with the advent of cannons, the walls - which had been impenetrable except by the Fourth Crusade for over 1000 years - no longer offered adequate protection from the Ottomans. The Fall of Constantinople finally came after a two-month siege by Mehmed II on May 29, 1453. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Paleologus, was last seen entering deep into the fighting of a over-whelmingly outnumbered civilian army, against the invading Ottomans on the ramparts of Constantinople. Mehmed II also conquered Mistra in 1460 and Trebizond in 1461. |

––– ♦ –––

| Legacy and Importance |

|

It is said history is written by the winners, and no better example of this statement is of the treatment of the Byzantine Empire in history - an empire resented by Western Europe, as shown by the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade. The 20th century has seen an increased interest by historians to understand the empire, and its impact on European civilization is only recently being recognised. Why should the West be able to perceive its continuity from Antiquity and thus its intrinsic meaning in the modern world - in so lurid a manner, only to deny this to the "Byzantines"? Called with justification "The City," the rich and turbulent metropolis of Constantinople was to the early Middle Ages what Athens and Rome had been to classical times. Byzantine civilization itself constitutes a major world culture. Because of its unique position as the medieval continuation of the Roman State, it has tended to be dismissed by classicists and ignored by Western medievalists. And yet, the development and late history of Western European, Slavic and Islamic cultures are not comprehensible without taking it into consideration. A study of medieval history requires a thorough understanding of the Byzantine world. In fact, the Middle Ages are often traditionally defined as beginning with the fall of Rome in 476 (and hence the Ancient Period), and ending with the fall of Constantinople in 1453. In commerce, Byzantium was one of the most important western terminals of the Silk Road. It was also the single most important commercial center of Europe for much, if not all, of the Medieval era. The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 closed the land route from Europe to Asia and marked the downfall of the Silk Road. . This prompted a change in the commercial dynamic, and the expansion of the Islamic Ottoman Empire not only motivated European powers to seek new trade routes, but created the sense that Christendom was under siege and fostered an eschatological mood that influenced how Columbus and others interpreted the discovery of the New World. Byzantium played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy. Its rich historiographical tradition preserved ancient knowledge upon which splendid art, architecture, literature and technological achievements were built. It is not an altogether unfounded assumption that the Renaissance could not have flourished were it not for the groundwork laid in Byzantium, and the flock of Greek scholars to the West after the fall of the Empire. The influence of its theologians on medieval Western thought (especially on Thomas Aquinas) was profound, and their removal from the "canon" of Western thought in subsequent centuries has, in the minds of many, only served to impoverish the canon. The Byzantine Empire was the empire that brought widespread adoption of Christianity to Europe - arguably one of the central aspects of a modern Europe’s identity. This is embodied in the Byzantine version of Christianity, which spread Orthodoxy (the so-called "Byzantine commonwealth," a term coined by 20th century historians) throughout Eastern Europe. Early Byzantine missionary work spread Orthodox Christianity to various Slavic peoples, and it is still predominant among the Russians, Ukrainians, Serbians, Bulgarians, people of the Republic of Macedonia, as well as among the Greeks. Less well known is the influence of the Byzantine religious sensibility on the millions of Christians in Ethiopia, the Coptic Christians of Egypt, and the Christians of Georgia and Armenia. Robert Byron, one of the first great 20th century Philhellenes, maintained that the greatness of Byzantium lay in what he described as "the Triple Fusion": that of a Roman body, a Greek mind and an oriental, mystical soul. The Roman Empire of the East was founded on Monday 11 May 330; it came to an end on Tuesday 29 May 1453 - although it had already come into being when Diocletian split the Roman Empire in 286, and it was still alive when Trebizond finally fell in 1461. It was an empire that dominated the world in all spheres of life, for most of its 1,123 years and 18 days. Yet although it has been shunned and almost forgotten in the history of the world up until now, the spirit of Byzantium still resonates in the world. By preserving the ancient world, and forging the medieval, the Byzantine Empire's influence is hard to truly grasp. However, to deny history the chance to acknowledge its existence, is to deny the origins of Western civilization as we know it. |

––– ♦ –––

| Byzantine Art |

|

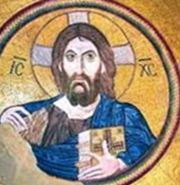

Byzantine art is generally taken to include the arts of the Byzantine Empire from the foundation of the new capital of Constantinople (now Istanbul) in AD 330 in ancient Byzantium to the capture of the city by the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The territory of the Byzantine Empire originally encompassed the entire eastern half of the Roman Empire around the Mediterranean Sea but shrank to little more than Greece, part of southern Italy, the southern Balkans, and Anatolia after the Islamic invasions of the 7th century. In the period after the 12th century, the empire comprised little more than Constantinople and a few other outposts. The influence of Byzantine art, however, extended far beyond these borders, because arts derived from Byzantium continued to be practiced in parts of Greece, the Balkans, and Russia into the 18th century and, in some isolated monasteries, to the present day. Moreover, it was during the 12th century that the influence of Byzantium on western European art, already an important factor in the preceding period, reached its zenith and played a truly generative role in the development within Romanesque Art of a greater naturalism in style and humanism in content. Byzantine art could play this role because, throughout its long history, it maintained a connection with the artistic heritage of Greek and Roman art and architecture; it preserved and transmitted much of this heritage to the West until Western artists were able to approach antiquity directly. Early Byzantine art must be considered in relation to the Early Christian condemnation of pagan idolatry and the consequent reluctance to depict sacred Christian figures and stories. Although many notable exceptions exist, figural scenes were usually avoided and were presented in an allusive symbolic mode or were embedded in complex programs that made the veneration of single images nearly impossible. The magnificent mosaic program (546-48) of San Vitale in Ravenna focuses on the ritual of making offerings to Christ. He is depicted in the apse mosaic, receiving a model of the church from Bishop Ecclesius and bestowing a martyr's crown on its patron, Saint Vitalis. The same theme of offering is picked up both in Old Testament scenes of the offerings of Abel, Abraham, and Melchizedek and the famous twin panels of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora. Image VenerationAfter about 550, such restraint weakened, and in 7th-century church decorations, such as those of the churches of Saint Demetrius at Salonika and Santa Maria Antiqua in Rome, small isolated panels depicting single figures begin to appear at or near eye level. The style of these works continues the tendency evident in the Theodora panel of San Vitale toward large-eyed, elongated figures arranged in formal hieratic frontal poses, almost compelling veneration. More important, these images are similar in style and subject matter to ICONS, whose great importance in Byzantine art dates from this period. Both panels and icons similarly invite overt veneration of the holy figures portrayed in this manner. The Iconoclastic CrisisIn the next century the fear of idolatry that haunted the Byzantines broke out in Iconoclasm (726-843), the imperially sponsored wholesale destruction or obliteration of all art that depicted sacred figures, and the violent persecution of its opponents. Subsequently, religious art was limited mainly to images of the cross and of symbolic birds and plants, as in the 8th-century mosaics of Hagia Eiene (Church of the Holy Peace) in Constantinople. Secular art, however, seems, to have continued throughout the period and served as the foundation for the revival of Christian figural art in the succeeding period. Macedonian RenaissanceToward the end of the 9th century, Byzantine religious art entered its "second Golden Age," often called the Macedonian Renaissance for the ruling dynasty. The term may be too strong, but it does correctly indicate the extent to which the art of the period, in both subject matter and style, often draws directly and deliberately on the Hellenistic and Roman classical heritage. Monumental art again exhibited relatively naturalistic and strongly modeled three-dimensional figures, often characterized by a restrained dignity and noble grandeur, as in the mosaic of the Virgin and Child (867) still in place in the apse of Hagia Sophia. Within the newly developed and standardized Byzantine Greek-cross church, such figures were organized into consistent programs best preserved today in the churches of Hosios Lukas in central Greece (c.1000) and Daphninear Athens (c.1100). At Daphni, the Pantocrator - Christ as Lord of the Universe - appears at the summit of the central dome, and the Virgin is represented in the apse above the altar as the instrument of Christ's incarnation. Below her the church on Earth is represented by the saints, and around the upper parts of the vaults were arranged major scenes from the life of Christ. These scenes, which closely correspond to the major feast days of the Byzantine religious calendar, are often called a feast cycle and act as reminders of events in the life of Christ that are also reflected in the daily liturgy. Spread of Byzantine ArtDuring the 11th and 12th centuries the mosaic system was carried by Byzantine mosaicists to Russia (Hagia Sophia at Kiev, 1043-46) and in Italy to Venice (Saint Mark's, after 1063) and to Norman Sicily. (Palatine Chapel, Palermo, 1140s; Monreale Cathedral, 1180s). At the same time, Byzantine art began to develop a much stronger humanistic approach, now with a greater concern for naturalism and for conveying a strongly emotional quality. In icons such as Our Lady of Vladimir (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), produced in Constantinople about 1130, the Virgin no longer displays her divine child to the people but interacts with it in more human terms, as the child turns toward her and clings to her neck. The use of Frescoes in churches spread throughout the Balkans; clearly derivative of lost works in Byzantium itself, they show an extreme emotional intensity.  "Pantocrator" in Daphni, Athens, Greece Palaeologan Mosaics and FrescoesAfter the capture and sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the development of Byzantine art was severely disrupted, but not altogether ended. However, the period following the reestablishment of the empire (1261) in Constantinople under the Palaeologan dynasty saw a brilliant revival of intellectual life. Its greatest artistic monument is the splendid mosaic and fresco program of the small church of Saint Savior in the Chora in Constantinople, dating from the first decade of the 14th century, which combines a refined decorative quality with a delicate emotional sensibility, as in the striking Anastasis fresco in the pareccleseion, depicting Christ descending into Hell. Both the decorative and emotional qualities characterize the last phase of Byzantine painting. They occur, for example, in the frescoes of the churches of Mistra, the mountainside capital of the despotate of Morea in southern Greece. These frescoes date from the decades around the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 and mark the end of Byzantine art as such.  The Anastassis fresco Thereafter, Christian art languished in the former Byzantine lands, which were all subject to Turkish rule; only in the young Russian state, where the Orthodox church remained dominant, did the artistic tradition inspired by Byzantium continue to develop. In Byzantium the applied arts of manuscript illumination, ivory carving, metal work, enamel work, and textile manufacture held an importance and achieved a magnificence seldom matched in other cultures. They were produced largely for the imperial court, for the altars of churches, or as diplomatic presents for export, such as Saint Stephen's Crown of Hungary. Such objects were avidly sought by Western medieval rulers and churchmen. They frequently served as models for works later produced locally and survive in large numbers in the major European and American collections. From the 6th to the 12th century, Byzantium held a monopoly on the production of silk textiles, which were treasured in the West. Illuminated ManuscriptsFor the development of Byzantine art the inherently conservative medium of Illuminated Manuscripts had a particular importance in preserving ancient traditions. Only a handful of the magnificent books produced in the pre-Iconoclastic period survive, of which the Rossano Gospels (Archiepiscopal Museum, Rossano, Italy), and the famous Vienna Genesis manuscript.(Nationalbibliothek) are the outstanding examples; both contain many separate miniatures painted on purple parchment and may be dated to the 6th or 7th century.  The Vienna Genesis manuscript Secular books were also profusely illustrated. The Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan preserving a text of Homer's Iliad (c.500) and the Vienna Nationalbibliothek a pharmaceutical manual, De materia medica (512), by the Greek physician Dioscorides. A strongly classical element is particularly characteristic of illustrated manuscripts, perhaps reaching its high point during the Macedonian Renaissance of the 10th century. In the famous Paris Psalter (c.950; Bibliotheque Nationale) a portrait of David composing the Psalms is placed in a rich pastoral landscape closely paralleling the Hellenistic-Roman art of Pompeii. Ivories and EnamelsClassical subjects and a classicizing style may also be found in a certain type of secular ivories produced during the 10th century, such as the Veroli Casket (Victoria and Albert Museum, London), with its scenes taken from classical literature (Euripides) and mythology.  The Veroli Casket Ivories were more commonly intended to serve as book covers or altar objects. Christian subjects were presented in a sober version of the classicizing idiom, with hieratically arranged rows of holy figures, as in the beautiful 10th-century Harbaville triptych (Louvre, Paris). This noble classicizing style is even more characteristic of Byzantine enamel work executed in Cloisonne, in which the glowing gemlike colored enamels enclosed in burnished gold heighten the splendor. Examples of such works, among the most prized possessions of the courts and treasuries of Europe, include the jeweled Pala d'Oro altarpiece (mostly 12th century) in Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice, and the reliquary at Limburgan der Lahn (964-65), decorated inside and out with enamel figures. |

––– ♦ –––

| Byzantine Architecture |

|

Although many local variants existed in different regions of the empire during most of the 4th and 5th centuries, Byzantine religious architecture used the two basic structures developed in early Christian Architecture - longitudinal-plan basilicas, which served as meeting places for the eucharistic service, and centralized-plan buildings, which served as baptisteries and as martyria (memorials over tombs of martyrs). BasilicasBasilicas continued in use into the 6th century; splendidly preserved examples, with magnificent mosaics in the apse above the altar, may be seen at Sant'Apollinare in Classe (549), near Ravenna in northern Italy and at Saint Catherine's monastery at Mount Sinai (c.560).  Interior of St Apollinare, Ravenna, Italy At this time, however, during the reign of Emperor Justinian I the Great (527-65), centralized plans began to be used for congregational churches as well as for martyrs' shrines, probably because of the growing importance of the cult of relics. Important examples of such centralized churches are Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople (527-36) and the stylistically related octagonal church of San Vitale in Ravenna (532-47). Greek Cross ChurchesFew major architectural projects were undertaken during the three troubled centuries following the death of Justinian in 565. During the late 9th- and 10th-century revival, however, the classic Byzantine church, generally small in scale but richly decorated with mosaics, was developed. The typical church comprised a high central dome with four vaults arranged about it to form an equal-armed cross known as the cross-in-square or the Greek-cross church. This period also saw the increasing on the practice of closing off the chancel from the rest of the church with an Iconostasis, a screen hung with icons and with a large central door. This arrangement was intimately bound up with the Byzantine liturgy; the architectural setting intensified the mystery of the Mass, most of which was performed in secret behind closed doors but included splendid processions that were symbolic manifestations of the divinity. The classic Middle Byzantine Greek cross church continued to be built without fundamental change down to the modern period, became the standard for the Slavic churches of Russia and the Balkans. |

––– ♦ –––

| Byzantine Clothing |

The essential articles of Byzantine dress are simple and easy to construct. The primary article of dress was called a tunica. The tunica served as the basic undergarment of both men and women, or the only garment for the working class and poor. The main over-garment worn both by men and women is called the dalmatica. This garment began a t-tunic, but became more tailored in eighth century. The essential line of a dalmatica is triangular, with narrowing sleeves or flaring sleeves. Another over-garment for women only is the stola. The stola is unchanged from Roman times. Prior to seventh century the stola was the only over-garment for women. In seventh and eight centuries the stola developed bell-shaped sleeves and became indistinguishable from the dalmatica. Outer wear consisted of three different style cloaks, the paludamentum in semi-circle or trapazoid shapes and the paenula, a full circle cloak. The Byzantines were very fond of vibrant, bright colors, reserving royal purple for the emperor and empress. Their dress is richly ornamented with embroidery and trim. The highest classes ornamented with jewels, particularly pearls. Fabrics consisted of linen for tunicas and some dalmaticas, stolas, and cloaks; Silk for richer tunicas, dalmaticas, stolas and cloaks. Dalmaticas and cloaks were of wool as well. Egyptian cotton was found in tunicas, though very rarely. Shoes and accessoriesVery little is known of Byzantine footwear, no examples have survived, and images show little. Royal footwear does show jewels and embroidery. Accessories to wealthier Byzantine dress include: Sudarium, an elaborate embroidered handkerchief; contabulatim, a long embroidered cloth, sometimes fan-folded and wound around the body; pallium, a very rich, hem length, jeweled court tabard, worn by men; and the superhumeral, an elaborate embroidered and sometime jeweled collar. When extensions wear added to the superhumeral, it became a pallium. |

––– ♦ –––

| Byzantine Food |

The civilization of Constantinople is sometimes misunderstood as a poor imitation of classical Greece and Rome. From the perspective of medieval western Europe, however, Constantinople was a city of magic and mystery. Early French epics and romances tell of the wondrous foods, spices, drugs, and precious stones that could be found in the palaces of Constantinople. Byzantine culture never ceased to develop and to innovate, and this is certainly true of its cuisine. Among favored game were the gazelles of inland Anatolia, and wild asses, of which herds were maintained in imperial parks. The seafood most appreciated by the Byzantines was botargo (salted mullet roe), and by the twelfth century they were familiar with caviar. Fruits largely unknown to the ancient world but appreciated in Constantinople included the aubergine (eggplant), lemons (via Armenia and Georgia), and the orange. The Byzantines were the first to try rosemary as a flavoring for roast lamb; they first used saffron in cookery. These aromatics, well known in the ancient world, had not previously been thought of as food ingredients. Byzantine cheeses included mizithra (produced by the pastoral Vlachs of Thessaly and Macedonia) and Cretan prosphatos. As for bread, the bakers of Constantinople were in a most favored trade, according to the ninth century Book of the Eparch, a handbook of city administration: "bakers are never liable to be called for any public service, neither themselves nor their animals, to prevent any interruption of the baking of bread." Mastic and anise were among the aromatics used in baking. The distinctive flavor of Byzantine cookery is best represented by sweets and sweet drinks. There are dishes that we would recognize as desserts: grouta, a sort of frumenty, sweetened with honey and studded with carob seeds or raisins; and rice pudding served with honey. Quince marmalade had been known to the Romans, but other jellies and conserves now made their appearance, based on pear, citron, and lemon. The increasing availability of sugar assisted the confectioner's inventiveness. Rose sugar, a popular medieval confection, may well have originated in Byzantium. Flavored wines, a variant of the Roman conditum (spiced wine), became popular as did flavored soft drinks, which were consumed on fast days. The versions that were aromatized with mastic, aniseed, rose, and absinthe were especially popular; they are distant ancestors of the mastikha, vermouth, absinthe, ouzo, and pastis of the modern Mediterranean. A remarkable range of aromatics, which were either unknown to earlier Mediterranean peoples or used only as perfumes or in compound drugs, were added to Byzantine spiced wines: spikenard, gentian, yellow flag, stone parsley, spignel, valerian, putchuk, tejpat, storax, ginger grass, chamomile, and violet. Two influences combined to produce the great range of powerful flavors at the heart of Byzantine cuisine. One was the Orthodox Christian church calendar, with its numerous fast days on which both meat and fish were proscribed: the rich (including rich abbots and ecclesiastics) gave their cooks full rein to produce fast-day dishes as piquant and varied as could be imagined. Byzantine pease pudding, a fast-day staple, was aromatized with nutmeg, an eastern spice unknown to the classical Greeks and Romans. The second influence was that of dieticians. Ancient Greek and Roman dietary manuals had been addressed to experts. The Byzantine ones, however, were written for nonspecialists. As in classical Greece and Rome, physicians relied on the theory of the "four humors" (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile) and prescribed diets aimed to achieve a proper balance of humors in each individual. The effect of each ingredient on the humors was therefore codified so that the desired balance could be maintained by a correct choice of dish and by a correct adjustment of ingredients, varying for the seasons, the weather, the time of day, and each individual's constitution and state of health. Dieticians sometimes recommended vegetarian meals, eaten with vinegar or other dressing. Spices and seasonings became ubiquitous, used both during the cooking process and at the table to amend the qualities of each dish. Fresh figs, if eaten in July, must be taken with salt. A daily glass of conditum, strong in spikenard, was recommended in March; anisaton, anise wine, was appropriate for April. These Byzantine dietary manuals are important sources of culinary history; botargo is first named in the eleventh century by the dietician Simeon Seth, who notes that it "should be avoided totally." The earliest work in this tradition is Anthimus's On the Observance of Foods, compiled by a Byzantine physician for a gothic monarch in the early sixth century. The food of the poor of Constantinople was no doubt limited, though a poetic catalog of a poor family's larder (Prodromic Poems 2.38–45, probably twelfth century) includes numerous vegetables and locally grown fruits along with a considerable list of flavorings: vinegar, honey, pepper, cinnamon, cumin, caraway, salt, and others. Cheese, olives, and onions perhaps made up for a scarcity of meat. Timarion, a satirical poem of the twelfth century, suggests salt pork and cabbage stew as being a typical poor man's meal, eaten from the bowl with the fingers just as it would have been in contemporary western Europe. The staple of the Byzantine army was cereal food—wheat or barley—which might be prepared as bread, biscuits, or porridge. Inns and wine shops generally provided only basic fare. However, in the sixth-century Life of St. Theodore of Syceon, a Byzantine text, there is a reference to an inn that attracted customers by the quality of its food. Annual fairs were a focus for the food trade. Important fairs were held at Thessalonica and Constantinople around St. Demetrius's day. Constantinople was known for specialized food markets. Sheep and cattle were driven to market to Constantinople from pastures far away in the Balkans, and eastern spices followed long-established trade routes through Trebizond, Mosul, and Alexandria. The populist emperor Manuel (1143–1180) liked to sample the hot street food of the capital, paying for his selection and waiting for change like any other citizen. Medieval travelers to Byzantium did not always like the strange flavors they encountered. Garos, the fish sauce of the ancient world, which was much used as a flavoring by the Byzantines, was unfamiliar and often unappreciated. Many disliked resinated wine (comparable to modern retsina), which was simply "undrinkable" according to one Italian traveler, Liutprand of Cremona. However, foreigners were seduced by the confectionery, the can-died fruits, and the sweet wines. William of Rubruck, a thirteenth-century diplomat who was looking for presents to take from Constantinople to wild Khazaria, chose dried fruit, muscat wine, and fine biscuits.  The Last Supper from St Apollinare The cuisine of the Byzantine Empire had a unique character of its own. It forms a bridge between the ancient world and the food of modern Greece and Turkey. In Constantinople astonishing flavor blends were commonplace. For example, roast pork was basted with honey wine; skate was spiced with caraway; wild duck was prepared with its sauce of wine; there was garos, mustard and cumin-salt, and black-eyed peas served with honey vinegar. Old recipes were adapted to new tastes; whereas ancient cooks had used fig leaves, thria, as edible wrappings for cooked food, during Byzantine times vine leaves were used in recipes, the precursors of modern dolmades. When the future emperor Justin II (reigned 518–527) walked from his Dalmatian homeland to Constantinople in 470 as a penniless young man seeking service in the Imperial guard, we are told that he had nothing but army biscuits to keep him alive on his long march. This paximadion, or barley biscuit, makes the perfect link from the ancient, via the Byzantine, to the modern period. A classical Roman invention, popularized in the Byzantine Empire, it has many modern descendants: the Arabic bashmat, baqsimat, the Turkish beksemad, the Serbo-Croat peksimet, the Romanian pesmet, and the modern Greek paximadi.  Food legacyBeyond the old boundaries of the Byzantine Empire, Byzantium's greatest legacy to western cookery may be summed up in these four things:

|

––– ♦ –––

| Sources: |

|

♦ Encyclopedia of food and Culture. Byzantium ♦ Crystalinks. The Byzantine Empire ♦ Warren Treadgold. "A History of the Byzantine State and Society", Stanford, 1997 ♦ Helene Ahrweiler, "Studies on the Internal Diaspora of the Byzantine Empire", Harvard University Press, 1998. |