Battle of Svindax(Battle of Phasiane) |

year: 1022Autumn 1022 |

| Victory of the Byzantine army over the Iberians and integration of the Iberian region in the empire | ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ |

|

enemy: Iberians (Georgians)

|

location: In the region of Phasiane in NE Asia Minor, in modern Kars district of Anatolia.

|

accuracy:

●●●●●

|

|

battle type: Pitched battle |

war: Iberian war |

modern country:

Turkey |

| ▼ The Byzantines(emperor: Basil II Bulgaroktonos) | ▼ The Enemies | |

| Commander: | Emperor Basil II | Ruler of Iberia Giorgi I |

| Forces: | 40,000 | Outnumbered |

| Losses: |

| Background story: |

| In 1021 Emperor Basil II marched with a large army to northeastern Asia Minor to reclaim the Byzantine territories (around the old principality of Taik or Tao) annexed by the ruler of Iberia and Abasgia (i.e. Georgia and Abkhazia) George I. George avoided meeting in person the emperor and also avoided confronting him in battle even though he also had a strong army. The Byzantine army overtook the Iberians as they retreated near the lake of Palakazio and a bloody battle was fought there; the Byzantines were victorious. But the victory in that battle was indecisive, as much of the Iberian army fled to the mountains, and shortly afterwards it was reinforced with forces from other principalities of the Transcaucasia. Although the Iberians had already been expelled from the disputed areas, Basil was furious that he could not close the open issues with the Iberians and reacted harshly: he ordered his units to disperse and plunder the country of the Iberians with the order not to spare neither old men nor women nor children, to kill them all. Thus, twelve provinces were ravaged and deserted. The atrocities committed then are described in the darkest colors in the medieval chronicles of Georgia and Armenia. The Byzantine army then left the area and encamped in Trabzon where it spent the winter. The following year, the Iberians appeared willing to negotiate, while Basil himself, although primarily a warlord, always preferred solutions that could be given through diplomacy. Thus, in early 1022, consultations began to reach an agreement. Basil sought to secure the occupation of the territories of the Taik (or Tao) hegemony and the surrounding areas inherited by David the Kuropalatis, while the Iberians wanted at all costs to prevent a new destructive invasion by the Byzantines. But then a serious development took place: A military uprising broke out against the emperor in Cappadocia, led by the distinguished general Nikephoros Xifias (who was then general of the army of the East) and Nikephoros Phokas (nicknamed Varytrachilos –son of the rebel of the 970s Vardas). The motives for this revolt are unclear. Maybe it had to do with the fact that Basil did not include them in his campaign in Iberia (why indeed?) although the campaign took place essentially in the backyard of these two. Or it may have had to do with the resentment lurking among the “dynatoi” (the mighty ones) of Asia Minor who had seen their vast fortunes diminished by the policies of Basil II. In any case, the uprising gathered many supporters in central Asia Minor and for a moment it seemed that it could become a serious threat to the emperor, who was fortified at the fortress of Mazdat. Many Iberian and Armenian local lords were among the supporters of the insurgents, and this raised the reasonable suspicion that the revolt was incited by George, the Iberian ruler. Basil appointed Theophylaktos Dalassinos as the new general of the East and sent him to suppress the uprising. Under unspecified circumstances, on the 15th of August 1022, Nikephoros Varytrachilos was killed by the men of Xifias and a little later Xifias himself was arrested by Dalassinos. Thus the revolt had an anticlimactic end, leaving behind the shadow of the involvement of the Iberians. Negotiations with the Iberians continued in a climate of distrust, but they were dragging on and it was now clear that George was deliberately delaying. At the same time, George sent an army to Phasiane (or Basiani), an area north of Manzikert, to recapture it. All the Armenian and Georgian chroniclers of the period agree that George lingered until he found the right opportunity to attack. Unfortunately for him, he was dealing with one of the most ruthless and effective leaders of Byzantium, and the trick of deceiving the enemy through negotiations was very old and very familiar to the Byzantines. In fact, it was analyzed in military manuals such as the Strategikon of emperor Maurice and the Taktika of Leo VI. The emperor in the end was raged with the games of the Georgians and decided to start the war again. |

The Battle: |

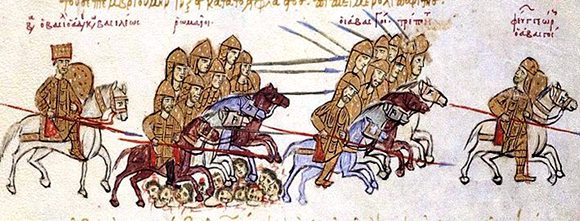

The victory over Iberians from the Skylitzes manuscript It seems that Basil was caught unprepared, believing that the enemy would continue the tactic of avoiding fighting. So the army was not in battle formation. Nevertheless, the Iberians attacked with their cavalry and although their attack was disorganized and rather impulsive, it was initially victorious and drove a part of the Byzantine army to flee. The Iberians, however, made the mistake of thinking that the battle had been won after this first success, and began looting the enemy camp (although this may have been deliberately allowed to trap them – another age-old tactic). At the same time, their king George began to give instructions so that the emperor Basil would not escape! The Byzantines counterattacked and then the Iberians first came in contact with the Varangians. Georgian chroniclers report with awe how their army was taken by surprise by these formidable warriors that no one could resist. The Iberians tried to regroup, but their cavalry was rendered useless as their horses were loaded with booty. The battle turned into a disaster for them. Their losses were devastating. Around the end of the battle, Basil applied his favorite tactics of terrorizing the enemy: he promised a fee a for the heads of Georgian horsemen. Piles of heads were erected in the roads of Phasiane, as a heinous trophy of victory. After the battle, George immediately declared his submission and asked the emperor to forgive him, fully accepting the Byzantine rule in Taik, Fasiani and other neighboring areas. The Byzantine emperor actually forgave him and allowed him to keep a part of his principality. |

Aftermath: |

| A separate administrative division for Iberia was founded, the Iberian thema. The treaty stipulated that the infant son of George I Pagratios would remain in Constantinople for 3 years as a hostage. Pagratios was returned to his parents after the 3 years. George probably planned to regain the lost lands after the death of Basil in 1025, but he died prematurely in 1027. The area remained in Byzantine hands until the 1070s when the Seljuk invasions began. |

|

|